The Window of Tolerance for PTSD

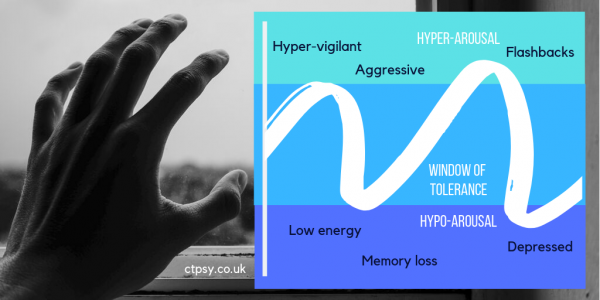

The Window of Tolerance is a concept introduced by psychologist Daniel J. Siegel, to explain the level of comfort and stability for a trauma survivor to manage everyday life.

Above the Window of Tolerance is a state of hyper-arousal, where you feel overwhelmed by memories of your trauma and associated triggers, and your body is pushed into ‘fight or flight’ mode. You can feel angry, overly alert and unable to rest, because your body is being flooded with hormones.

You’ll often experience unwanted flashbacks or images, and find yourself prone to outbursts. It may be particularly difficult to be in crowded or busy environments, where you feel overstimulated and poised to react to a threat.

Below the Window of Tolerance is a state of hypo-arousal: you feel numb and depressed, with very little energy, and you may avoid socialising with other people or freeze in situations. You’ll need to sleep, your blood pressure may drop, and your digestion might even slow down.

As with hyper-arousal, you’re not able to function properly. You may have feelings of dissociation, even memory loss, and you cannot think clearly. You may even resort to self-harm.

‘Traumatised adults are prone to revert to primitive self-protective responses when they perceive certain stimuli as a threat.’ Bessel A. Van der Kolk, writing in Trauma and the Body (2006).

Unfortunately, your Window of Tolerance can shrink when you suffer trauma or difficult life experiences. You may feel much less able to cope than you would have done five or ten years ago. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is nothing to be ashamed of, but it can be successfully treated.

By working with a therapist, you can expand that Window of Tolerance and increase your comfort zone. When you come close to going beyond your personal limits, you can apply the techniques you’ve learned to help bring you back to a safe level.

What can help bring you back to the Window of Tolerance?

- Mindfulness helps you focus on sensations and the space around you. Feel the sensation of the ground under your feet; the chair or bed you might be sitting on; the background noise of traffic, chatting, music or birdsong.

- If background noises overwhelm you, move to a quieter space, or plug in some noise cancelling headphones and listen to a playlist or podcast. Listen to the voices and their rhythms. Take deep breaths as you listen. Close your eyes.

- Be aware of your body’s physical reactions to triggers and unwanted thoughts, even if these aren’t comfortable to think about – you might have shoulder tension, stomach pain, a headache, or a dry mouth. What can you do to relieve that pain? Could a hot water bottle or a cool drink help?

- Psychosomatic symptoms are very common. You may not be aware of all your physical symptoms, but your therapist can usually spot them – for example, you might clench your fists regularly without realising. When you exhibit these kinds of symptoms when thinking about trauma, it’s known as sensorimotor processing. Even your posture can change in reaction to traumatic memories.

- Validate your feelings, whether they’re signs of hyper-arousal or hypo-arousal. If you’re a parent with a child who has experienced trauma, help them to identify their feelings and let them know it is okay to bring them up.

- Look for self-soothing actions to adopt. Again, these can be based around sensations: a weighted blanket can add comfort. Favourite smells, either perfumes, room diffusers or candles, can calm you. Give yourself a few options to choose from, and have travel-ready versions for when you’re out and about – a scarf or wrap can stand in for a blanket. A favourite scent can fit into a mini atomiser, or you could gather samples from perfume counters.

- Think about the timeframe you’re in. Traumatic memories hold power because they make you feel like you’re back in that situation, no matter how long ago it was, or the distance in miles you are from where the incident took place.

- If you’re thinking about a school-age memory and you’re now 45, look how far you’ve come since your school days. You aren’t the same person you were then. You’ve lived longer out of school than you were in it. You don’t have the same haircut; you might not have the same friends. You aren’t confined to those walls.

Other treatments for PTSD include Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprocessing (EMDR) and the Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT).

Reading List

Janet, P. (1925). Psychological Healing: A Historical and Clinical Study, Vol. 1. London: G. Allen & Unwin.

Ogden, P. et al (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. (1999). The Developing Mind. New York: Guilford.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (1987). Psychological Trauma. Washington DC: American Psychiatric.

Written by guest contributor Polly Allen for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

Why Hoarding Can Be a Psychological Issue (and how to get help)

It may seem like a quirk of someone’s personality, or a sign of sentimentality, that they save up their possessions and can’t bear to throw anything away. Many people struggle to give up items they’ve bought, made or been given, however much clutter they might accrue over the years. In fact, when it presents a health and safety issue to the hoarder and their family or housemates, hoarding becomes a psychological problem that cannot be ignored.

The NHS has recognised hoarding as a medical condition since 2013, and it is estimated at least 1.2-3 million British adults may be hoarders to some degree. Those over the age of 55 are three times more likely to have hoarding tendencies, but many sufferers will have shown early signs as teenagers.

There is a difference between hanging onto things you love (no matter their cost or value) for good memories or reassurance, and being unable to remove them without feeling loss or distress. As humans we attach emotions to objects quite easily – we think about what they represent, from holiday souvenirs to our child’s first pair of shoes or their favourite toy. It’s perfectly normal to feel emotional when we see key items, and to gather memory boxes of things we hang onto.

It’s also fun to become a collector as a hobby, whether you’re into film memorabilia, rare books, or the latest trainers – something young people seem particularly obsessed with. Building up a collection is usually a solo hobby, but going to conventions and trade fairs or talking on forums can add a social element.

The difference comes when you can attach meaning and emotions to what might normally be passed on: sweet wrappers; threadbare socks; clothing you’ve never worn and you can’t fit into. We live in a throwaway society, but we’re gradually returning to a ‘make do and mend’ mindset, turning our backs on single-use plastics and fast fashion, but that doesn’t mean we need to build up infinite piles of things we never use. Keeping things to rework or fix is fine if you always get round to using them, but not if they just take up space and you feel uneasy or unwell at the thought of letting them go.

A hoarder’s inability to declutter will eventually make their home unsafe, with floor to ceiling piles of anything from newspapers to cleaning products. Simply going in there and removing items isn’t enough; this can provoke the hoarder’s anger and make them lash out or cut off contact. The psychology behind the hoarding must also be tackled, and emotional support must be offered.

There are added complications when other people share the living space – family members and housemates can suffer as a result of the hoarding, and may face anxiety themselves. Television presenter Jasmin Harman spoke out about her mother’s chronic hoarding in a 2011 documentary, My Hoarder Mum and Me, and has continued to raise awareness of hoarding ever since.

Hoarding can be tied to other mental health issues, particularly anxiety and depression, but also Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Your childhood experiences can also be related to hoarding tendencies – if you grew up in poverty but later earned a lot of money, you might accumulate things to make up for the years you went without. In an extreme example, many concentration camp survivors have been known to hoard food, as they are terrified of being on starvation rations again.

Some people even hoard animals – either rescue pets or shop-bought pets – and, despite being wanted in the household, this is harmful to the animals. Though the owners mean well and aren’t trying to be cruel, the animals usually have to be removed to receive proper care.

Hoarding can be treated using a combination of talking therapies, such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, and practical sessions with experts on decluttering. The therapy element is important because decluttering alone won’t stop the behaviour; real change comes from altering the mindset and the core beliefs of the hoarder, and freeing them from emotional associations with the things they hoard.

Written by guest contributor Vikram Das for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

No-Fault Divorce: An End to the Blame Game

Married and civil partnered couples in England and Wales will no longer have to blame each other for the end of their relationship, with the introduction of no-fault divorce due to become law soon.

The existing system can cause unnecessary conflict between the separating couple and any children they have. Finding fault, and combing through evidence of that fault, is both emotionally draining and time-consuming, and unsurprisingly can affect family life. A new bill is currently being tabled in the House of Commons to change this.

Currently there are five different reasons, or ‘facts’, you can cite in a divorce case:

- Adultery

- Behaviour (‘the respondent has behaved in such a way that the petitioner cannot reasonably be expected to live with the respondent’)

- Desertion

- Two years’ separation (with both parties consenting to divorce)

- Five years’ separation

The court then has to examine the evidence of reported conduct or separation. With the no-fault option, couples would have the autonomy to decide their relationship has broken down irrevocably. The Law Society is in favour of this change.

Critics may argue this could lead to partners divorcing before they have worked on their difficulties and sought help, but this is not about rushing people towards the decision to stay together or separate. It is about reducing the stress, time and costs after that decision has been made.

At the moment one half of the couple can also contest the divorce, which is rare, but can be used as a tactic by abusers to exert control. By also removing the opportunity to contest the divorce, lawmakers could potentially help abused partners escape their abusers quicker, and cause less trauma in the process.

Speaking on the changes to be made, Justice Secretary David Gauke said, “It cannot be right that our outdated law creates or increases conflict between divorcing couples.”

The change in the law was brought about after a public consultation, involving divorcees, lawyers and expert charities including Coalition for Marriage, Families Need Fathers, Stonewall and Women’s Aid.

Written by guest contributor Vikram Das for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

The Most Important Stories from Mental Health Awareness Week

How did you spend Mental Health Awareness Week? Maybe you took part in an event, shared something on social media, or spoke to a colleague who’s had a difficult time. However you marked it, the week was awash with fascinating stories in the media to increase our understanding of mental health conditions, many focusing on the theme of body image.

Here are some of the stories that stood out for us:

Distress Brief Intervention

A new intervention for adults experiencing a mental health episode has been successfully trialled in four areas of Scotland and will now be rolled out to cover 16 and 17-year-olds. Distress Brief Intervention has been implemented in GP surgeries and A&E departments across Aberdeen, the Borders, Inverness and Lanarkshire. It involves responding appropriately to early signs of mental distress and creating a ‘distress plan’ with patients, which will help with future episodes.

Early intervention is key to normalising mental health conditions and reducing their severity by building support networks and coping strategies for patients before an episode begins.

Body Image and Self-Harm

In a survey of more than 4,500 adults by the Mental Health Foundation, it has emerged that 13% of adults have experienced suicidal thoughts or feelings because of their body image. Of that 13%, the number of LGBT people reporting suicidal thoughts or feelings due to body image was particularly notable: 39% of those were bisexual and 23% were gay or lesbian. What’s more, 10% of women and 4% of men have self-harmed because of their body image.

If you are experiencing thoughts like these, or acting on them, it’s time to talk to someone. There are many types of talking therapy that can help you safely explore the root of these feelings, assess your core beliefs, and challenge negative thoughts towards your body.

A Postcode Lottery for Treatment

Mental health charity Mind revealed the growing postcode lottery of NHS spending on mental health treatment. The lowest spending regions were Surrey Heartlands (£124.48 per person, per year), Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin (£134.77) and Gloucestershire (£137), whilst the highest spending areas allocated over £200 per person, per year.

At Christine Tizzard Psychology, you don’t have to be restricted by your postcode. Our psychologists work in many areas of the UK, from Surrey and Sussex to Liverpool and Leeds.

Mental Health Research Losing £1.5bn in Funding

Miricyl, a charity which campaigns for mental health research, has argued the government’s UK Research and Innovation allocates funding in a way that discriminates against their cause.

The argument from Miricyl concerns UKRI’s match funding strategy; as only 3% of mental health research is funded by charitable donations, this is the matched figure, whereas Miracyl notes these types of health problems affect society and the economy so much that they equate to 16% of all illnesses. It remains to be seen whether UKRI’s actions can be deemed unlawful.

Three Quarters of Finance and Banking Professionals Won’t Use Support Provided by Employers

For this study, Morgan McKinley surveyed 1,100 people in banking, finance and commerce. Their results reveal that many employers aren’t clear enough on their formal policies for mental health support, and this type of illness is still stereotypically thought of as a ‘weakness’.

We’d like to see workplace health policies robustly cover severe stress, anxiety, depression and other psychological issues that may affect staff. This, coupled with a culture change, could create a more emotionally open and resilient workforce, without risking burnout.

Written by guest contributor Vikram Das for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

Forest Bathing: Not Just a Wellness Fad

You may have seen a lot in the media about forest bathing, the latest wellness trend to hit the UK. In recent years we’ve become accustomed to hygge (a Danish and Norwegian word for cosiness and warm feelings, usually through spending time with family and friends) and fika (a Swedish word for a coffee or tea break and snack, taken with friends or colleagues).

But suddenly forest bathing is everywhere; this Japanese practice, known as shinrin-yoku, has nudged us away from auto-pilot routines of rolling news coverage, smartphone addiction and competitively busy calendars. The Japanese adopted forest bathing as a way to get into nature, with the phrase coined by Forestry Minister Tomohide Akiyama in 1982 as a promotion for the country’s vast forests.

The concept really works: surrounded by a canopy of trees, listening to birdsong or crunching leaves underfoot, you do feel you’re immersed in the forest itself. But there are some rules: don’t get absorbed by your phone or camera; don’t try and plan a route; just aimlessly wander at a slow pace and see where you end up.

Being around nature is scientifically proven to have a positive effect on our moods. Writing for the Global Landscape Forum’s Landscape News, journalist Gabrielle Lipton explained: ‘Phytoncide chemicals emitted by trees can help reduce cortisol levels, strengthen the immune system, lower blood pressure, boost creativity and aid sleep. Exposure to the non-pathogenic bacteria in the soil, Mycobacterium vaccae, can release more serotonin in the brain.’

What’s more, research from Aarhus University in Denmark has revealed that children with the least access to green space are 55% more likely to develop a psychiatric disorder in later life, compared to their peers with regular access to green space, such as forests, parks or gardens. The study was conducted on one million Danish people and looked at the green space available nearby when they were aged 0-10. It followed the subjects from 1985-2013 and monitored them against the likelihood of developing 16 common psychiatric disorders.

The good news is that you don’t need your own garden or acres of forest to feel the benefits – if you only have a small park or slice of woodland to access, you aren’t disadvantaged. Of course, being outside has lots of general advantages: you can’t beat a bit of fresh air and that feeling of clearing your head and taking a walk or sitting on a bench without being chained to a desk or just in the confines of four walls. The change of scene and removal of indoor distractions can also tie into mindfulness. Forced to get away from technology and urban sprawl, you give yourself the chance to breathe again.

Forest bathing shouldn’t be a fad; this is a hugely positive lifestyle change that doesn’t cost any money but can help everyone.

Written by guest contributor Polly Allen for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

How Therapy and Assistance Dogs Help Children with Autism

There’s growing interest in therapy and assistance dogs for children with autism, thanks to the good reputation of these specially trained dogs for helping in everyday situations and during meltdowns.

Christine Tizzard Psychology has Gus, a dog who works calmly with autistic patients during assessments. Gus brings a sense of reassurance and familiarity to them, and can often distract patients from worries or fixations they bring into the room.

Whilst many studies recommend buying a therapy or assistance dog for an autistic family member, this isn’t always possible – you may not have the space, time or money to care for a dog; you may live in rented accommodation without permission to have pets; someone in your family could be allergic to dogs (guinea pigs have also been studied as an alternative). Demand for therapy or assistance dogs also outstrips supply across the UK.

However, if you are able to take on a dog, there are benefits for the whole family:

- Assistance or therapy dogs can be trained to respond to verbal or visual cues (such as a repeated action, obsession or outburst) and interrupt this behaviour by nudging or touching the child. This distraction method helps break the cycle and brings comfort.

- Autistic children sometimes wander off, causing distress to parents and carers, especially in unfamiliar surroundings. Assistance dogs can find children quickly.

- A parent or responsible adult should hold the lead of an assistance dog in public and give commands, but secondary leads can give a more confident autistic child the chance to ‘take the reins’, without risking the child or the dog’s safety.

- Dogs provide loyalty and friendship. Unlike fiercely independent cats, dogs also need to be taken for walks, providing a social element for the whole family. Walks usually involve meeting people who take an interest in the dog and start a conversation, which will help a child with lower verbal abilities or social anxiety.

- An autistic child can help care for their dog – for example, brushing them, fetching water or playing fetch. The routine and responsibilities will help them immensely.

Therapy or assistance dogs must be individually matched to children and families; this isn’t an overnight process, but it can have a transformative effect on an autistic child’s behaviour and the frequency of meltdowns.

Just make sure you choose a dog provider and trainer registered with either Assistance Dogs UK or Assistance Dogs International (nationally accredited organisations).

Written by guest contributor Vikram Das for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

Understanding Loneliness in the Elderly

Loneliness is a growing issue for people of all ages, with loneliness in the elderly a particular concern for academics, psychologists and charities. But what makes older people lonely, and how can we help them overcome it?

Family Dynamics

Society has changed both positively and negatively in the last few decades, due to technology, innovation and the economy. We take on more overtime work than before (an average of 9.6 hours a week, according to a 2017 study by Totally Money). We also retire later, spend more time commuting (according to the TUC in 2018) and take work home with us on smartphones and laptops, so it’s not surprising we have less quality time with older family members, whether to see them socially or support them day-to-day.

When they need practical help or assisted living arrangements, we may be hundreds of miles away, and it may not be feasible for them to move in with us or for us to move closer to them. Finding the right sheltered accommodation or care home isn’t easy, either; it involves great upheaval for an elderly person.

Regaining a Social Life

An older person’s social life can dwindle for many reasons: perhaps their existing friends have moved away, gone travelling or become weekday carers for their own grandchildren. If someone chooses to retire and has previously depended on workmates for their social life, it can take a long time to adjust to retirement, and a challenge to reconnect with old colleagues outside the office.

The same goes for someone whose social life may have revolved around their partner; grief for the loss of that partner comes alongside grief for the companionship and social life that is lost.

Developing new friendships isn’t an overnight process and, as in the days of making friends at school or work, some of these friendships will quickly fizzle out whilst others will be slow-burners. However, there are several sure-fire ways to meet new people, whether or not they become close friends:

- Volunteer – this doesn’t have to be a heavy commitment, but a couple of hours a week at a charity, hospital, museum or even helping a community group is a good way to start. If that seems too much, try volunteering as a marshal at a big one-off charity event or a community clean-up.

- Find common interest groups – use Meetup.com or search local newspapers and magazines for details of nearby groups, whether that involves walking football, crafts, books, theatre trips or archaeology.

- Get a small part-time job – pick something manageable and customer-facing. It may not be well-paid compared to previous jobs, but it’s the chance to get out of the house and earn some ‘pocket money’. Think paper rounds (especially for those who wake early), working in a community café, or taking a couple of weekly shifts at the local garden centre, with the bonus of staff discount on all those lovely plants.

If there’s very little available locally, particularly if an older person lives in a rural area, remember there could be many others nearby in a similar situation. Consider looking further afield for groups or jobs, or try setting up a group and promoting it locally with posters, newspaper listings and a Meetup.com listing, which is free.

Emotional Wellbeing

Loneliness can have huge repercussions on someone’s emotional health, leading them to feel anxious, depressed, withdrawn and lethargic. Dealing with these emotions will take time, especially as people may be reluctant to admit they are lonely, but talking therapy can help uncover the feelings and core beliefs behind that loneliness.

Core beliefs may seem dramatic – for example, ‘all my friends will abandon me’ or ‘I am not a fun person to be around’ – but they sit at the heart of a person’s emotional distress. In Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), we challenge these core beliefs, relate them to periods in our life, and weigh up the evidence for and against them being true.

Physical Health Effects of Loneliness

Loneliness also brings physical health considerations. Lonely people are more likely to have a stroke, coronary heart disease and even dementia; they are also more likely to enter residential care earlier, take more medication, and have a greater risk of falls than their peers who do not report being lonely. It is said that loneliness is as bad for your health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Let’s not forget that a socially active person would probably have a better support network around them for any mental or physical health needs, too. Having people on hand to travel to appointments or check in from time to time has got to be a bonus for overall health; if they can’t physically be there, regular phone calls, messaging and video calls make a difference as well, and a break in frequent contact can alert a friend or relative that something’s wrong.

Ignoring loneliness won’t make it go away; there are serious mental and physical effects to consider, and we can break the cycle by encouraging interaction, peer networks, self-esteem boosts and talking therapy.

Written by guest contributor Vikram Das for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

Dealing with Your Child’s ‘Bad’ Friends

Do you remember the intensity of making friends and developing friendships when you were young – the agony and ecstasy of searching and finding your friendship group? You probably found a few ‘bad’ friends along the way that your parents (or even your peers) disapproved of, either because they appeared to have a negative influence on you, because they were a bit wayward or different, or because they genuinely caused trouble.

You might also remember clashing with your parents over this kind of friend’s bad influence. Chances are, your parents’ opposition only pushed you further towards your friend, and that’s completely natural. As we progress through childhood and teenage years into adulthood, we learn to make our own judgements – some will be correct, others a total disaster, but we should all gain more autonomy as we age and mature.

So how can you manage these ‘bad’ friendships as a parent or carer? When should you intervene? It can feel like a minefield.

Sound Out Other Opinions

Use other parents and carers as a sounding board to put your feelings in context. Have they met the friend in question? Do they have any concerns? These conversations are more fruitful if your child is a pre-teen, as you’ll have more contact with other parents and you’re all more likely to have met the dodgy friend at playdates or birthday parties.

The older your child, the less you’ll be let into their lives, but that doesn’t stop you talking to fellow parents and sharing advice. Forums like Mumsnet, Netmums and Gransnet can be useful. There are plenty of parents and carers who have been in your shoes and can share their experiences of tackling peer pressure and intense friendships.

Also talk to any older siblings, neighbours or cousins of your child, who may be able to weigh in and share their insight. If your child shuts down your initial conversations about the bad friend, they may open up to someone closer in age.

Welcome the Friend into Your Space

Show willing by welcoming the ‘bad’ friend at home or on trips out, so you can get to know them. This helps your relationship with your child, too, by showing you aren’t dismissing their friend outright.

If you suspect your child is drinking, smoking or similar because of this friend, having them under your roof could seem counter-productive, but you can potentially supervise from a distance, knowing where they are. We emphasise ‘from a distance’ here, because turning into an amateur spy is not going to help matters.

By sharing space with your child’s ‘bad’ friend, you may even change your preconceptions of them. Someone who initially comes across as rude or loud may just be socially awkward. Of course, getting to know the friend also means you may meet their parents, which can help matters further.

Be Curious but Respectful of Boundaries with Older Children

You’ll never stop worrying about your child – that’s the blessing and curse of being a parent – but you must remember they will reveal less about their lives as teenagers than they did when they were five or 10 years old. You may have to handle a Kevin the Teenager figure for a few years.

With hormones flooding their bodies and a shedload of exams to get through, not to mention the modern preoccupations of social media and the internet, teenagers feel under intense pressure to do everything and be everything. Though they sometimes act supremely confident, they are highly sensitive. If they feel you’re prying too much into their lives, you’ll know about it.

Keep a healthy level of interest in their hobbies, wellbeing, achievements and failures, but please don’t become a helicopter parent or cling to a nostalgic view of your child. They are casting off their childhood mould and developing their own personality, which is a case of trial and error. By all means, share things they may enjoy that don’t involve the friend, but don’t expect to be your child’s number one confidante.

Put Things in Perspective: Will This Jeopardise Their Future?

If your child’s behaviour becomes dangerous or self-destructive under this friend’s influence – for example, they are bullying other children together, getting into trouble with the police or their school marks and attendance have dropped significantly, you need to take action. Arrange to see their form tutor or class teacher and raise the issue.

There may be complex reasons for this behaviour, such as your child becoming a bully to avoid being targeted by the ‘bad’ friend. You need to understand the full story, and this is difficult if your own child is shutting you out. Getting the school involved will help you make progress.

However, if their behaviour is more like your own teenage rebellion, put it in perspective. Experimentation is part of growing up, and though it worries you now, it is likely to blow over. Stick to your usual ground rules, such as a set time to come home from a night out, and making sure they do chores and help out, but expect these rules to be tested, whatever friendship influences they have.

And the final word of reassurance? However you approach it, a troubling friendship may well peter out over time, anyway; a 2015 study by Florida Atlantic University found that only 1% of friendships formed by children aged 12-13 years old lasted five years, and 76% of friendships formed at this time lasted less than a year. Keep those statistics in your mind to feel more positive.

Written by guest contributor Polly Allen for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

Raising Awareness of Multiple Sclerosis on the Red Carpet

Whether you’re interested in films and celebrities or you couldn’t care less, there’s an undeniable buzz about the Oscars, especially in the strange times we live in, where there are more political twists and turns than a Hollywood thriller. So, imagine our surprise and delight on seeing actress Selma Blair, who recently announced her diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, walk the red carpet.

Blair’s bespoke diamond-embellished cane was as much a part of her outfit as her dress, hair and shoes. In fact, Vanity Fair magazine revealed her hair had been cut into a short bob not to fit with a trend, but to accommodate her condition – she now struggles to raise her arms to brush her hair, so a bob is a more manageable style. Her clothing, too, has to be more adaptable than before MS took hold.

On revealing her diagnosis, Blair wrote poignantly that ‘my left side is asking for directions from a broken GPS’. Answers came after five years of puzzling symptoms that came and went. MS is an autoimmune disease that affects the brain and the spinal cord, and the outcome stretches to the whole nervous system. For Blair, that means ‘I fall sometimes. I drop things. My memory is foggy’, and other debilitating symptoms like extreme fatigue, muscle spasms and pain. During a flare-up, those with MS can even find it hard to talk.

Inside the body, the immune system reacts wrongly to the protective substance surrounding nerve fibres. This substance, myelin, is treated as a threat and is attacked by the nervous system, leaving myelin damaged or stripped away from the nerve cells, which then causes scarring. Messages carried by the nerve fibres are damaged or unable to be passed on, and the nerve fibres themselves also become damaged.

Living with MS

An estimated 127,000 people live with MS in the UK; most will be diagnosed in their 30s-50s but, like Blair, may have had symptoms for many years before; the MS Society says 5-10% of those living with MS had their first symptom before they were 16 years old. MS affects nearly three times as many women as it does men, though it is not known why.

Despite the prevalence of MS and other autoimmune conditions, we do not normally see those who live with it in the public eye. When someone famous is willing to discuss their autoimmune condition, it can work wonders to increase public awareness and possibly help those with initial symptoms but no diagnosis. It can also bring comfort to those already diagnosed as they adjust to life with an autoimmune disease.

As Blair has found, there are adjustments to be made in work, at home, and in the everyday tasks the able-bodied take for granted; the time it takes to reach a stage of acceptance of any long-term illness depends on the individual and their support network of friends, family and colleagues. A difficult boss or a lengthy campaign for PIP benefits can cause immense stress, which worsens their symptoms and mood.

As well as physical support, such as a cane or wheelchair, and taking manageable exercise to fit with their fluctuating ability, it is clinically proven that people with MS can benefit from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). At Christine Tizzard Psychology, we also help with pain management through CBT, and have experience treating clients with long-term conditions.

Seeing Selma Blair on the red carpet, diamond-tipped cane in hand, and the slew of articles and discussions about MS since the Oscars, is both reassuring and inspirational.

Written by guest contributor Polly Allen for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).

Christine Tizzard Psychology is currently undertaking research on a possible link between PTSD and autoimmune disease. Click here for details.

Immersive virtual reality therapy helps treat autistic children’s phobias

A study at Newcastle University has found that immersive virtual reality programs can be used as therapy tools to treat phobias in children with autism. Having used virtual environments to try and conquer their phobias, nearly 45% of children in the study were free from these phobias six months after the study ended, suggesting this therapy provides long-term results.

A separate virtual reality study on a smaller number of adults with autism found it can benefit them too, with five out of eight participants left feeling more equipped to cope with their phobias in day-to-day life. Both studies were conducted with Third Eye NeuroTech.

The virtual reality environment in the study, called the Blue Room, was personalised to each of the 32 children aged 8-14 who took part. A psychologist accompanied each child for four sessions in the Blue Room, spread across one week, with their parents able to watch via video link. Having learned to approach their phobia through virtual reality scenarios, the children then faced their phobia in real life. Just two weeks after therapy, 40% of children showed signs of improvement in dealing with their phobia; this rose to 45% six months after treatment.

“People with autism can find imagining a scene difficult which is why the Blue Room is so well-received,” said Dr. Morag Maskey of the Instititute of Neuroscience at Newcastle University. “We are providing the feared situation in a controlled way, through virtual reality, and sitting alongside them to help them learn how to manage their fears.”

Though they may share some common fears or phobias with non-autistic children, such as a fear of dogs or balloons (both tackled in this study), children with autism may also have less well-known fears to overcome; for example, the noise of vacuum cleaners, blenders and hand dryers could all trigger intense panic. It’s estimated that 25% of autistic children suffer from fears and phobias; aside from this, a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can often go hand in hand with anxiety disorders.

Whilst this recent research hones in on the potential for managing phobias, using virtual technology to help autistic children is nothing new in itself, with over 20 years’ worth of studies from academics.

There are also several apps and programs available to help children approach new environments and practice common social situations, like using public transport or going to school. People with autism have difficulty blocking out external stimulation, and can be heavily affected by background noise, crowds, bright lights and other stimuli. Apps such as Floreo have been specifically designed to be guided by parents or therapists, allowing them to keep updated on a child’s progress.

Virtual reality can also be effective at communicating what it feels like to have autism, so those who don’t have the condition can understand its effects. The National Autistic Society created a video, Too Much Information, that can now be viewed with cardboard goggles in a 360-degree experience. To date, 56 million people have used the video to better understand the condition.

It’s great to see technology being harnessed to help the autistic community. With such positive research results, nobody can deny that technology is a valuable tool for psychologists, teachers and for families with an autistic child.

Bibliography

Morag Maskey, Jacqui Rodgers, Victoria Grahame, Magdalena Glod, Emma Honey, Julia Kinnear, Marie Labus, Jenny Milne, Dimitrios Minos, Helen McConachie, Jeremy R. Parr. A Randomised Controlled Feasibility Trial of Immersive Virtual Reality Treatment with Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Specific Phobias in Young People with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2019

Morag Maskey, Jacqui Rodgers, Barry Ingham, Mark Freeston, Gemma Evans, Marie Labus, Jeremy R. Parr. Using Virtual Reality Environments to Augment Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Fears and Phobias in Autistic Adults. Autism in Adulthood, 2019