The Window of Tolerance for PTSD

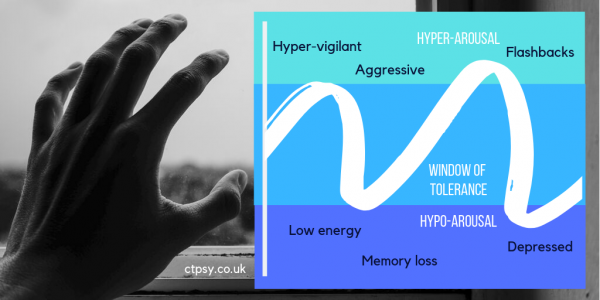

The Window of Tolerance is a concept introduced by psychologist Daniel J. Siegel, to explain the level of comfort and stability for a trauma survivor to manage everyday life.

Above the Window of Tolerance is a state of hyper-arousal, where you feel overwhelmed by memories of your trauma and associated triggers, and your body is pushed into ‘fight or flight’ mode. You can feel angry, overly alert and unable to rest, because your body is being flooded with hormones.

You’ll often experience unwanted flashbacks or images, and find yourself prone to outbursts. It may be particularly difficult to be in crowded or busy environments, where you feel overstimulated and poised to react to a threat.

Below the Window of Tolerance is a state of hypo-arousal: you feel numb and depressed, with very little energy, and you may avoid socialising with other people or freeze in situations. You’ll need to sleep, your blood pressure may drop, and your digestion might even slow down.

As with hyper-arousal, you’re not able to function properly. You may have feelings of dissociation, even memory loss, and you cannot think clearly. You may even resort to self-harm.

‘Traumatised adults are prone to revert to primitive self-protective responses when they perceive certain stimuli as a threat.’ Bessel A. Van der Kolk, writing in Trauma and the Body (2006).

Unfortunately, your Window of Tolerance can shrink when you suffer trauma or difficult life experiences. You may feel much less able to cope than you would have done five or ten years ago. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is nothing to be ashamed of, but it can be successfully treated.

By working with a therapist, you can expand that Window of Tolerance and increase your comfort zone. When you come close to going beyond your personal limits, you can apply the techniques you’ve learned to help bring you back to a safe level.

What can help bring you back to the Window of Tolerance?

- Mindfulness helps you focus on sensations and the space around you. Feel the sensation of the ground under your feet; the chair or bed you might be sitting on; the background noise of traffic, chatting, music or birdsong.

- If background noises overwhelm you, move to a quieter space, or plug in some noise cancelling headphones and listen to a playlist or podcast. Listen to the voices and their rhythms. Take deep breaths as you listen. Close your eyes.

- Be aware of your body’s physical reactions to triggers and unwanted thoughts, even if these aren’t comfortable to think about – you might have shoulder tension, stomach pain, a headache, or a dry mouth. What can you do to relieve that pain? Could a hot water bottle or a cool drink help?

- Psychosomatic symptoms are very common. You may not be aware of all your physical symptoms, but your therapist can usually spot them – for example, you might clench your fists regularly without realising. When you exhibit these kinds of symptoms when thinking about trauma, it’s known as sensorimotor processing. Even your posture can change in reaction to traumatic memories.

- Validate your feelings, whether they’re signs of hyper-arousal or hypo-arousal. If you’re a parent with a child who has experienced trauma, help them to identify their feelings and let them know it is okay to bring them up.

- Look for self-soothing actions to adopt. Again, these can be based around sensations: a weighted blanket can add comfort. Favourite smells, either perfumes, room diffusers or candles, can calm you. Give yourself a few options to choose from, and have travel-ready versions for when you’re out and about – a scarf or wrap can stand in for a blanket. A favourite scent can fit into a mini atomiser, or you could gather samples from perfume counters.

- Think about the timeframe you’re in. Traumatic memories hold power because they make you feel like you’re back in that situation, no matter how long ago it was, or the distance in miles you are from where the incident took place.

- If you’re thinking about a school-age memory and you’re now 45, look how far you’ve come since your school days. You aren’t the same person you were then. You’ve lived longer out of school than you were in it. You don’t have the same haircut; you might not have the same friends. You aren’t confined to those walls.

Other treatments for PTSD include Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprocessing (EMDR) and the Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT).

Reading List

Janet, P. (1925). Psychological Healing: A Historical and Clinical Study, Vol. 1. London: G. Allen & Unwin.

Ogden, P. et al (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. (1999). The Developing Mind. New York: Guilford.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (1987). Psychological Trauma. Washington DC: American Psychiatric.

Written by guest contributor Polly Allen for Dr Chrissie Tizzard, Chartered Consultant Psychologist, PsychD, BSc, MSc, C.Psychol, C.Sci, AFBPS. Dr Tizzard is the Clinical Director of Christine Tizzard Psychology (ctpsy.co.uk).